This article addresses robotic surgical procedure in which kidney cancer occurs in a congenital variation known as horseshoe kidney. Using robotic surgery, the cancerous tissue is removed while preserving healthy part of the kidney.

What Is Horseshoe Kidney?

A horseshoe kidney is congenital anatomic variation where the two separate kidneys —the right and left kidneys—are joined together at their lower ends, forming a connection in front of the main artery (aorta) and main vein (vena cava inferior). Since the fused kidneys resemble the shape of a “U” or a horseshoe, this anatomical configuration is referred to as a “Horseshoe Kidney.”

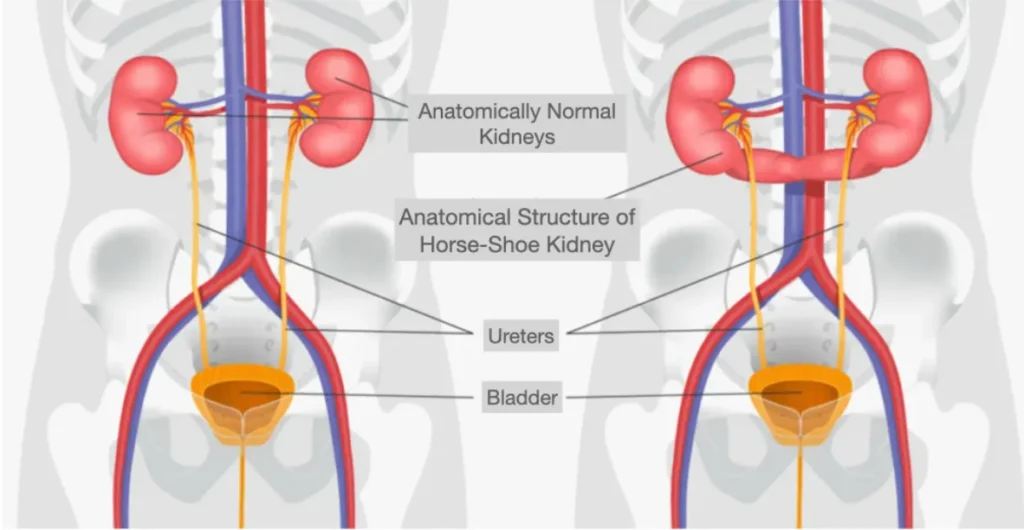

Figure 1: In a normal body, two kidney organs are located on either side of the main artery (aorta) and main vein (vena cava). Typically, each kidney receives one artery and one vein from the main vessels. In the other part of the figure, as described above, the right and left kidney tissues in a horseshoe kidney are fused together at their lower poles, forming a connection between them.

The lower poles of both kidneys, where they are fused together, are connected in front of the main artery (aorta) and main vein (vena cava). The ureters—tubes that carry urine produced by the kidneys to the bladder—pass in front of this fused kidney tissue and descend toward the bladder.

Is Having a Horseshoe Kidney a Bad Condition?

Of course not. Having a horseshoe kidney does not pose an increased risk for diseases such as cancer or renal insufficiency. In fact, a horseshoe kidney typically contains more kidney tissue than a normal kidney.

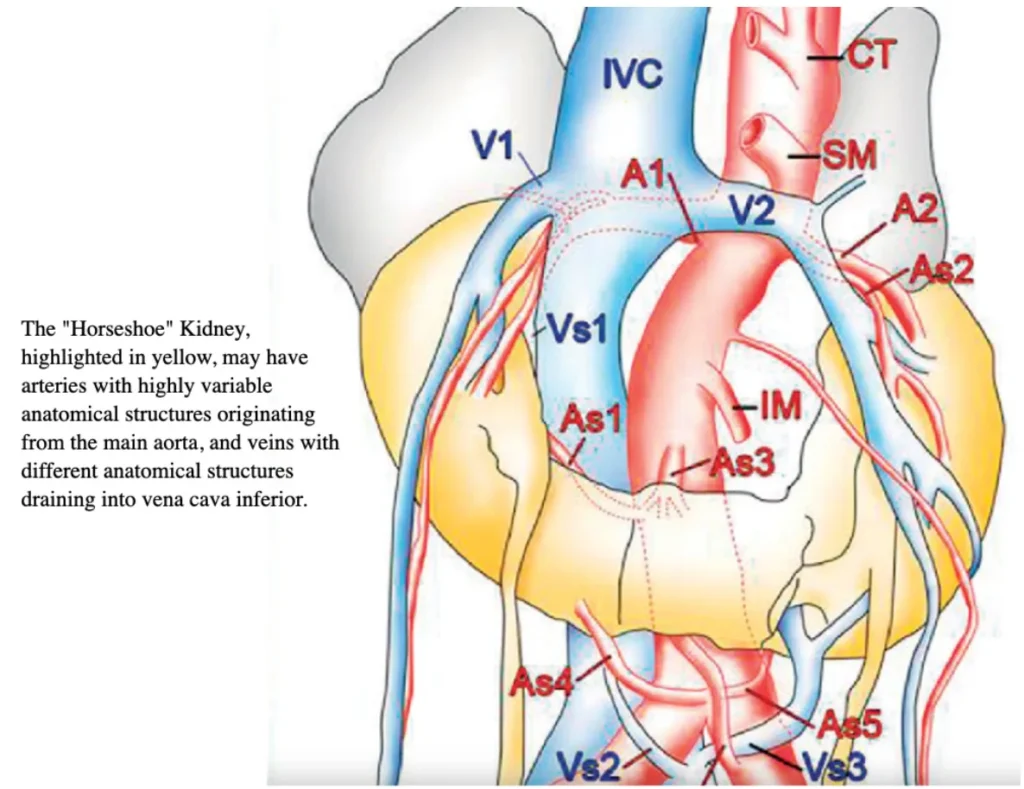

Figure 2: In a horseshoe kidney, the lower poles of the right and left kidneys are fused in front of the major blood vessels. This is referred to as congenital “fusion anomaly”

In this uniquely shaped kidney structure, instead of receiving a single artery and vein from the main blood vessels as in a normal kidney, there are often multiple arteries and veins, and their anatomical patterns can vary significantly. In horseshoe kidney anomalies, the number and arrangement of vessels branching from the aorta and vena cava can differ greatly from case to case.

Is Surgical Treatment Risky in Horseshoe Kidney?

Yes. In cases involving conditions such as stones, tumors, or cysts in a horseshoe kidney, the surgical approach is more complex compared to procedures performed on a normally structured kidney.

Why?

The fusion of the kidneys directly over the main artery (aorta) and main vein (vena cava), along with the presence of numerous atypical vascular structures, makes the surgical treatment of kidney conditions commonly seen in horseshoe kidneys (such as kidney stones, tumors, or cysts) more complicated and risky.

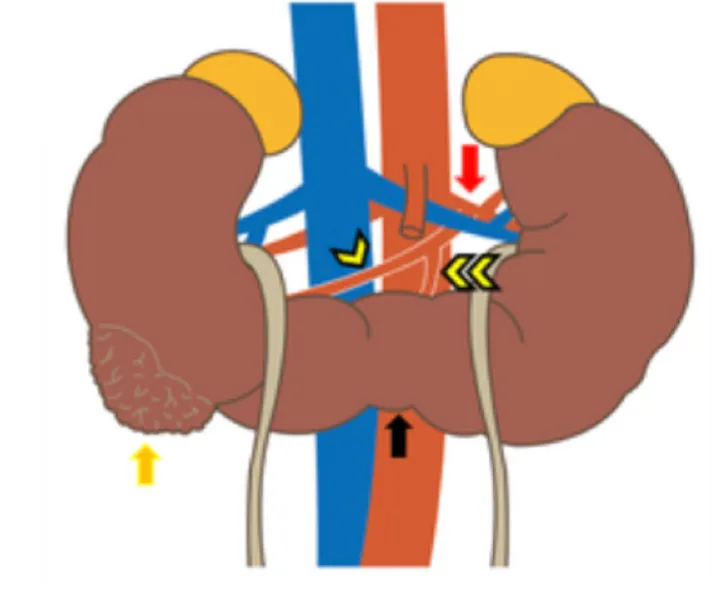

In horseshoe kidney surgery, it is crucial to control all arteries and veins supplying the fused kidneys in order to ensure proper bleeding control.

When performing surgery on one side of a horseshoe kidney (for example, to treat a tumor or stone), it is essential to also evaluate the vascular structures of the opposite kidney. This is because there are cross-vascular connections in the isthmus—the tissue connecting the two kidneys. Simply controlling the vessels on the affected side may not be sufficient, as vessels from the opposite kidney can still contribute to significant bleeding.

In addition to the complex blood supply, the collecting system inside the kidney—which gathers urine—can also have interconnections between the two sides. During surgery, unforeseen damage to this system may occur, potentially leading to postoperative complications such as urinary leakage.

Moreover, because the fused kidneys are located in close proximity to the aorta and vena cava, any surgical intervention must be performed with extreme caution to avoid unexpected injuries to these major vessels, which can result in severe bleeding.

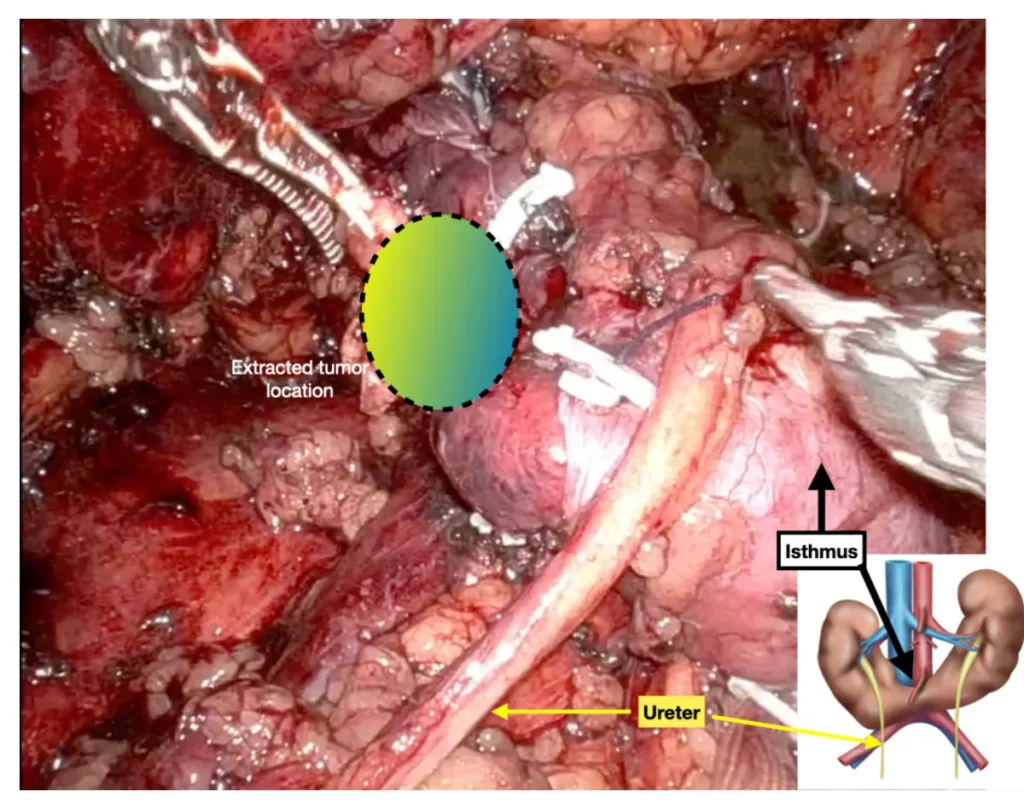

Lastly, in horseshoe kidneys, the ureters (tubes that carry urine from the kidneys to the bladder) pass in front of the connecting isthmus tissue. Therefore, during surgery, special care must be taken to avoid injuring or tearing these structures.

Figure 3: The illustration shows a tumor located on the posterior surface of the right kidney, along with its close anatomical relationship to the main artery (aorta) and main vein (vena cava). It also depicts the variety of vascular structures branching from these major vessels and supplying the horseshoe kidney. These anatomical differences and the presence of multiple vascular connections make surgeries involving horseshoe kidneys more complex.

How Should Preoperative Preparation Be Done for Surgery in a Horseshoe Kidney?

Conditions in a horseshoe kidney that may require surgical treatment commonly include:

- Hydronephrosis and non-functioning kidney

- Kidney tumor (renal cancer)

- Kidney stones

- Renal cysts

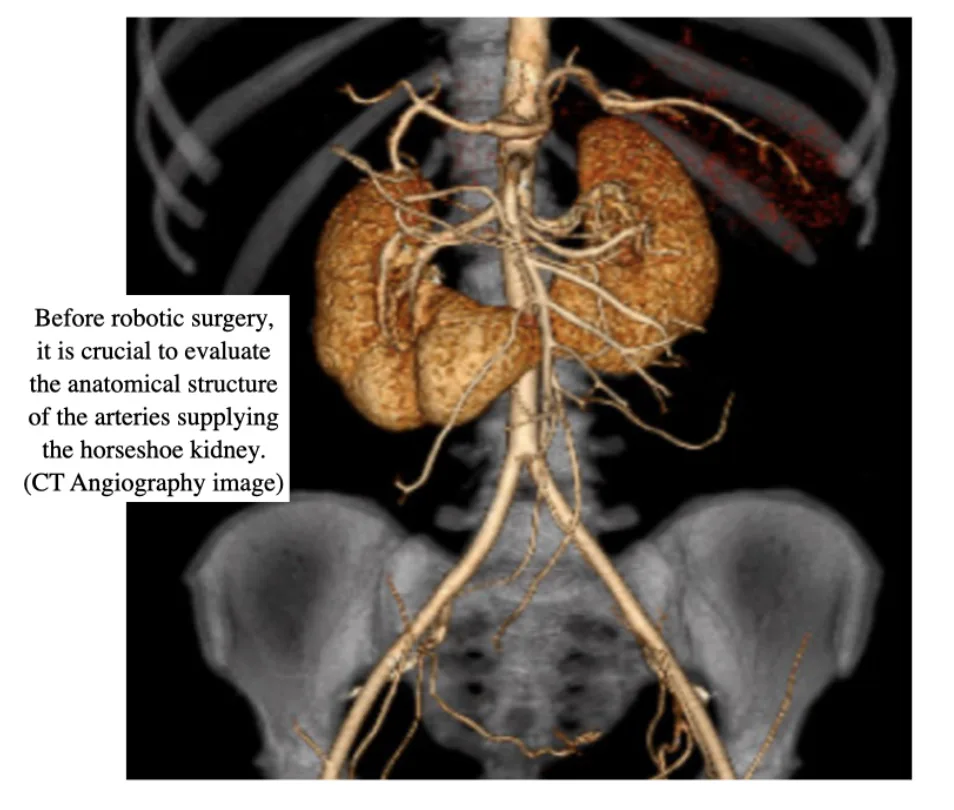

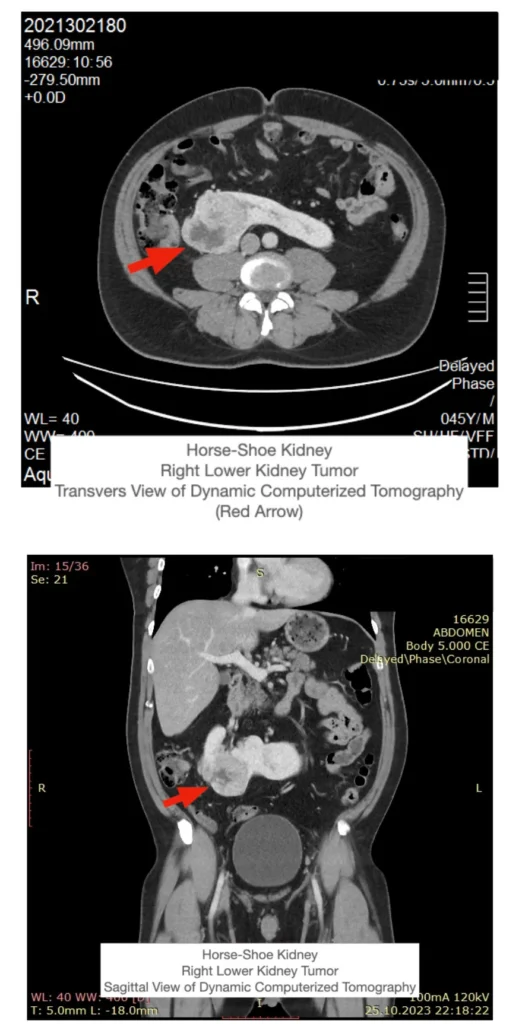

Regardless of the specific issue requiring surgical intervention, a horseshoe kidney must first be evaluated using dynamic imaging, including non-contrast, arterial, venous, and pyelographic phases of CT (computed tomography) and/or MRI (magnetic resonance imaging). This imaging approach clearly defines the horseshoe kidney anatomy and its relationship with surrounding blood vessels.

Figure-4: CT angiography shows vascular structures of horseshoe kidney in detail

Can Robotic Surgery Be Used for Kidney Cancer in a Horseshoe Kidney?

Yes, it can be safely and effectively performed. With adequate experience in robotic surgery, tumors in a horseshoe kidney can be treated in the same way as tumors in a normally structured kidney—by removing only the tumor while preserving the healthy kidney tissue.

In a normal kidney, the vascular structures are typically single or, in rare cases, double. However, in a horseshoe kidney, these vascular structures can be much more numerous and anatomically varied. Additionally, controlling the vessels on the side of the tumor may not be sufficient due to the presence of internal vascular connections that pass through the isthmus between the two kidneys. This makes the procedure more complex.

Therefore, robotic surgery can be successfully performed when accompanied by thorough preoperative evaluation using dynamic kidney MRI or CT imaging, which helps clearly define the anatomy and vascular relationships.

Figure 5 & 6: Kidney tumor in horseshoe kidney on the right side (lower posterior)

Can Robotic Supine Partial Nephrectomy Be Performed in a Horseshoe Kidney?

Yes, it can be successfully performed.

Particularly in the supine position (lying flat on the back, facing upward), we have gained significant experience through robotic supine RPLND surgeries performed in testicular cancer cases, which involve working around major arteries and veins. This experience allows us to apply the same supine robotic surgical approach in cases of cancerous tumors in horseshoe kidneys.

Using robotic surgery in the supine position, the tumor on either the right or left kidney can be removed while maximally preserving the healthy kidney tissue. During the procedure, vascular control can be effectively achieved not only for the affected (tumor-bearing) kidney but also for the healthy contralateral kidney.

Robotic Supine Partial Nephrectomy, also known as Robotic Supine Nephron-Sparing Tumor Excision, offers several significant advantages: minimal blood loss, very low postoperative pain levels, rapid recovery, and cosmetically favorable outcomes with only small keyhole incisions.

Figure-7: Short video and photograph of excised tumor side of horseshoe kidney (right lower posterior location)

To watch the “Robotic Supine Nephron-Sparing Tumor Excision” surgery for the treatment of horseshoe kidney cancer with robotic surgery, CLICK HERE.

Prof. Tibet Erdogru, M.D.

Uro-Klinik Istanbul